The happiest, most fulfilled, most balanced people I know have one thing in common: they are creators. I’m not just talking about artists–I’ve worked with all kinds of people who are in no way artists, but they are people who habitually approach their lives and work in a creative way. They look at a challenge on the job, or in their personal relationships, or in their day to day living, and see the chance to make something new happen instead of an impassable roadblock. They perceive imbalance, and through creative inquiry, find a way to adjust and create balance. They hear dissonant noise, and through experiment, find the way to make a pleasing chord.

These folks tend to know a lot about themselves and about people in general. Paradoxically, this leads them to know that there is a huge amount that they don’t know, not by a long shot. They are comfortable being curious about themselves and others. They aren’t afraid to delve into their own minds and see what surprises are there. They ask questions of others all the time, because they genuinely want to know the answers. They never consider that not knowing makes them look stupid or less-than.

So: a key part of my coaching involves celebrating curiosity, mine and my clients’. We ask questions together, and in those questions and the thoughts they lead to we find the fuel for the engine of positive change.

This curiosity, this openness to discovery relates to an ongoing discussion I’ve had for years with improvisers and other improv trainers. There is a fairly widely accepted improv “rule” offered to beginning improvisers that states: “no questions.” Now, I don’t really believe in many of the commonly accepted hard and fast improv rules, because they are all too easily broken, often with excellent results. The “no questions” rule was developed as advice to new improvisers, in an attempt to avoid a certain type of anxiety-based question that tends to shut down a scene.

Its an oversimplification, but I talk to my students about “good cholesterol” and “bad cholesterol” questions. The “bad cholesterol” questions are caused by blockage. The “good cholesterol” questions are lubricants that facilitate creative action.

In a typical rookie improv scene, you might see the following:

Character One and Character Two are on stage, and they are scared. Painfully conscious of the audience, the lack of a script, and the driving need to be funny and clever, they have both shut down. In a panic, they have forgotten all training. Character One turns to Character Two and says “What should we do now?”

Character Two: “I don’t know!” Both stare helplessly at each other, unable to think of anything “funny” to say…and the scene dies a slow and painful death.

Now, the problem with the “no questions” rule is that it is an attempt to fix the symptom, instead of addressing the real issue, in the above scenario. Before the question is asked, the two improvisers are already outside of the creative space, and adding that negative rule just adds to the things they are doing wrong. The last thing they need is to be wrong. But as soon as the question is asked, Character One remembers the rule, and beats herself up for breaking it. Character Two remembers the rule, and resents her for asking. Both players are stuck in a negative wasteland, now even farther outside of the creative space.

I shudder to think how many times I’ve seen that scene, and I’ll admit it–played that scene, in life and on stage.

Consider, then:

Character One and Character Two are on stage, and they are scared. Painfully conscious of the audience, the lack of a script, and the driving need to be funny and clever despite the advice that they don’t need to be either, they are both on the verge of shutting down. But suddenly Character One, remembering something from her training, breathes, relaxes, and opens up to really seeing Character Two. Without stopping to think, she says:

“When are we supposed to be at the party? It is tonight, right? Did you print out the email?”

“Character Two frantically pats his pockets…”Here it is! Yes, it’s tonight. And we’re late! We’ve got to hurry!” Character Two, delighted at having something to do, has remembered to say yes, and…

Suddenly the scene has someplace to go. Character One has asked not one but three questions, questions that came from a genuine acknowledgement of the mutual fear that she and her partner feel, and perhaps from some unconscious connection with something she noticed about her scene partner–perhaps a patting of the pocket or a look around the stage. Their adrenaline now has an outlet–frantic preparation for the party, or a mad dash for the car, or perhaps, some more of their training returning to them because of the release of their panic, they do a time dash to the party itself…

As they progress, these improvisers discover that the fear that fed this first scene is not necessary, that they won’t, in fact, die up there on stage. They learn that the “good cholesterol” questions that spring to mind are greatly liberating. As they get more comfortable, their natural curiosity can serve as the launch pad for hundreds of successful scenes.

So, the “no questions ” rule, for me, is a blind alley– a way that we can heighten the anxiety, rather than feed the natural curiosity of ourselves. So, in true coaching fashion, I leave you with a few questions:

Where are the equivalents to the “no questions rule” in your mind? What symptoms do they address, and what state of discomfort is the actual root of those symptoms? When do you find yourself open and curious when you face a challenge?

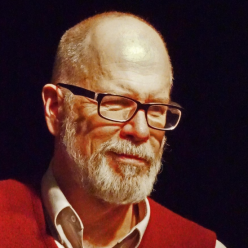

I am offering free sample coaching conversations. If you’d like to explore coaching with me, drop me an email at michaelburns@mopco.org.